Review of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye ‘Fly in League with the Night’ Tate Britain until 26th Feb 2023

I admit I was expecting portraits…what Lynette Yiadom-Boakye gives us is fiction. This is an exhibition that has you questioning what portraiture is, what fiction is, and what can painting do that words can’t and vice versa. For this is an exhibition that beguiles you with paint and then unsettles you with words.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Elephant, 2014

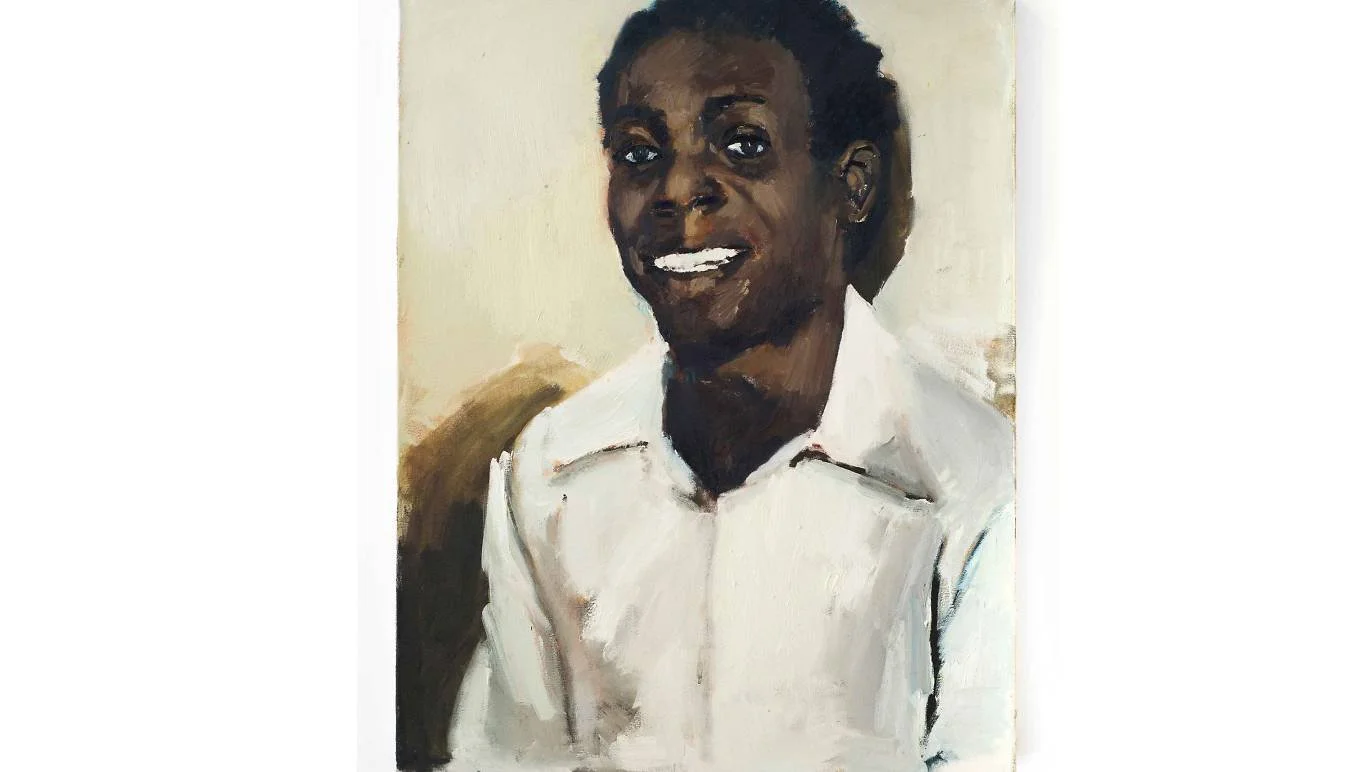

First though - the beauty of the paintings. Stunning in their simplicity, warmth and yes, truth. These, mostly, solitary figures either gaze out at us, or are self-absorbed, looking down or away from us, considering their own state of mind or state of being. These are not records of physical facts of appearance but portraits of the soul - fictitious but no less true. Perhaps it is the fiction that allows us to find ourselves in these paintings, to recognise our own humanity reflected back at us.

The warmth of the colours in most of the paintings shown here draws you in - the darkness of skin tones in dark spaces, gives an intimacy to the work, that pulls you closer, an approachability. The characters reside in a dark interior space of memory and introspection, but there seems to be hope - perhaps characterised by the warmth of colour - reddish browns, warm greys.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, A Passion Like No Other, 2012

Being fiction, there are many hints at narratives, including the poetic titles which ask us to question what we are looking at. This is work that requires time - to allow what we are seeing in the paintings and reading in the titles to float in our minds, to settle and allow poetic resonances connect words and images.

Yiadom-Boakye says: “I write about things I can’t paint and I paint the things I can’t write about.” She calls her titles “an extra brush mark”.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Condor and The Mole, 2011

Her work clearly draws on art historical references: Manet and Velasquez to name but two. She paints in oil on canvas, in a well worn tradition of portrait painting, but this show questions all those traditions. I find myself thinking of the first known portrait of a black sitter in Western European portraiture done by a woman painter Giovanna Garzoni in 1635 of Ethiopian royalty Prince Zaga Christ.1

It is a pleasure to see painting, direct and open, with no subterfuge, in a show at Tate at this time. It makes me hopeful yet for the future - not just of art but our desire to understand more about ourselves and each other.

Note:

Thanks to Katy Hessel for highlighting this work in her new publication The Story of Art without Men.